Dependency boundaries in TypeScript

Code projects of reasonable size tend to follow certain principles for abstracting complexity (aka architecture), making them easier to reason about and evolve. There are endless ways of doing so, some common examples being the Model View Controller (MVC) and Hexagonal architecture.

Those abstractions are set as a high-level system design (architectural blueprint), describing the responsibilities of each module and their relations between them (dependencies). The architecture will vary depending on the system's context and requirements, whether real-time data processing backed or a monolithic web application.

Keeping the day-to-day development aligned with the architecture blueprint can be challenging, especially if the project or organization grows fast. Pull-request reviews, mentoring, documentation, and knowledge sharing help, but it may not be enough.

In the context of TypeScript, we will discuss the importance of dependencies, the potential pitfalls when unchecked, and propose a solution for keeping the code in sync with the architecture dependency.

Let's get to it! 💪

Dependencies in TypeScript

In TypeScript, variables (functions, objects, values) can be imported/exported between files using the ES6 module syntax. Every variable annotated with export will be exported and can be imported using the import syntax.

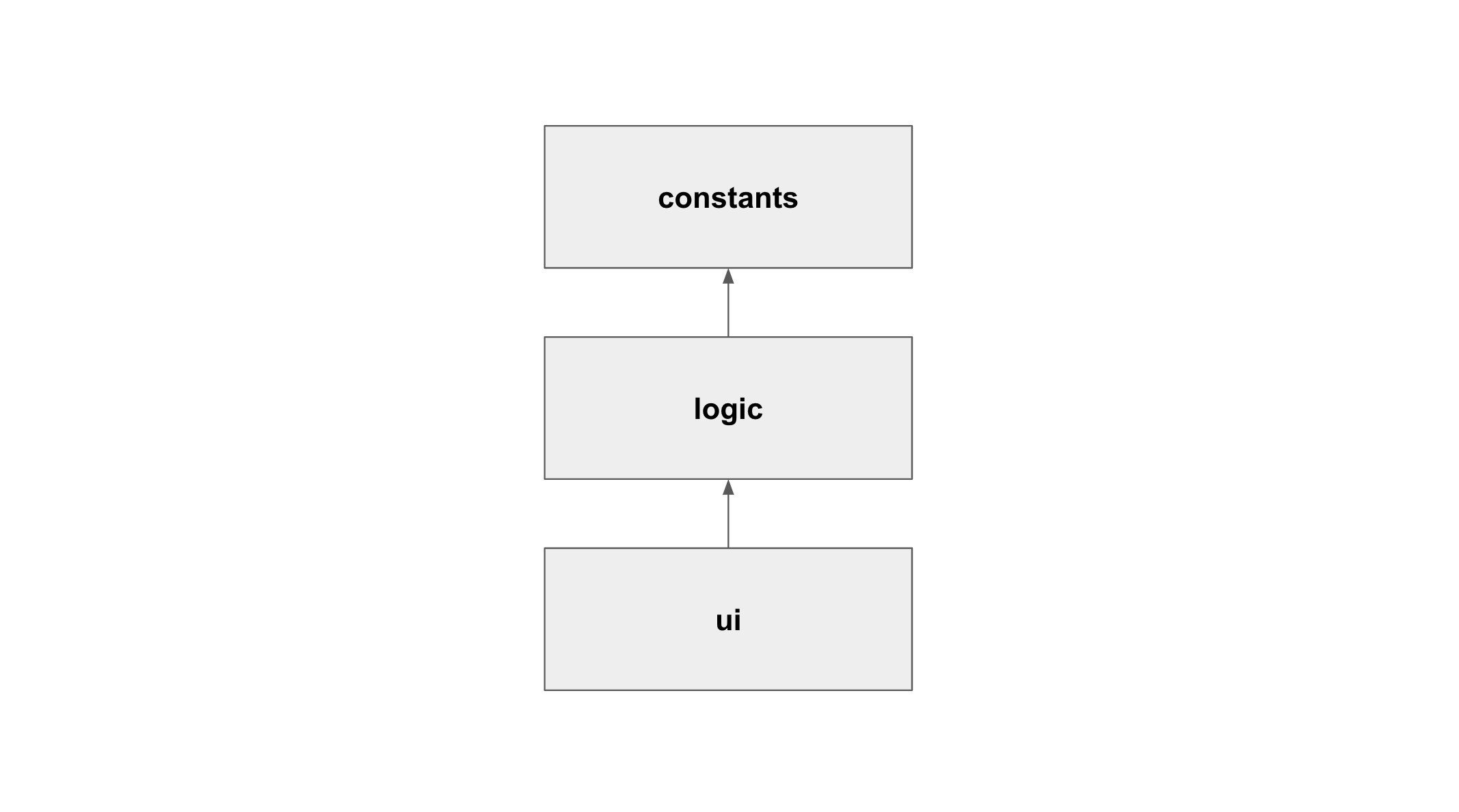

// constants.ts

export const USER = "Alain";

// logic.ts

import { USER } from "./constants";

export const greet = (): string => `Hi ${USER}!`;

// ui.ts

import { greet } from "./logic";

const html = `<h1>${greet()}</h1>`; // <h1>Hi Alain!</h1>This enables breaking up the functionality into modules, which can be organized following an architectural blueprint. It's important to note that importing local files and local or remote packages is possible, such as the ones available through npm.

This module syntax allows for great flexibility, imposing no restrictions on what can be exported or imported from anywhere. The dependency graphs are implicitly defined across the app.

As a project develops, that implicit dependency graph can grow unchecked, leading to some pitfalls.

Pitfalls of unchecked dependency management

One of the pitfalls of unchecked dependencies is that any program module can import and create a dependency towards any method exported within the codebase. Private and helper methods can be referenced out of their module, so keeping a public API of a module requires constant manual supervision.

Another pitfall is the freedom to import any third-party package. Third-party modules are great, as they can boost the development speed and avoid reinventing the wheel. On the flip side, too many dependencies can expose a project to security issues (due to outdated packages), conflicts between packages, and huge bundle sizes 😬

The third and main issue is that there is no way of programmatically enforcing or verifying that the code follows the architecture's dependency rules. Over time, the blueprint and implementation can grow apart to an extent where the reference architecture is not valid anymore.

This can void the intrinsic characteristics of an architecture, such as the separation between the view and controllers (containing the business logic) in MVC. It can make the business logic hard to test and reduces the ability to iterate the UI without breaking the business logic.

In the next section, we will look into how to make the dependencies explicit so that module internals can remain private, 3rd party dependencies kept under control and the architecture in sync with the code! 🔁

Adding explicit dependencies

To make the dependencies between modules explicit and set restrictive dependency rules, we'll use the good-fences package.

This package enables creating and enforcing boundaries in TypeScript projects and can significantly help mitigate the pitfalls described above. Let's see how we can use the package through an example!

In order to ensure that the implementation of the project matches and, over time, maintains the planned dependency graph, we will leverage the concept of fences (provided by the packages good-fences).

A fence defines how a module can interact with other modules and fenced directories and is created by adding a fence.json file to a TypeScript directory. Fences only restrict what goes through them (import, export, external dependencies), so within a fenced directory, there are no module import restrictions. Fences can also be tagged so they can be referenced from other fence configurations.

A practical example

The code is available in the following repo.

For the sake of an example, we'll use a simple React app, which follows the architecture of a store-driven UI, similar to React's presentational component pattern. The app provides the calculation of the nth number of the Fibonacci or Pell series (I said it was a simple app 😅).

The UI does not have access to the business-logic methods in the app, as they are abstracted behind the store. In addition, the business-logic code does not depend on any UI code, so the UI can evolve without touching the business logic.

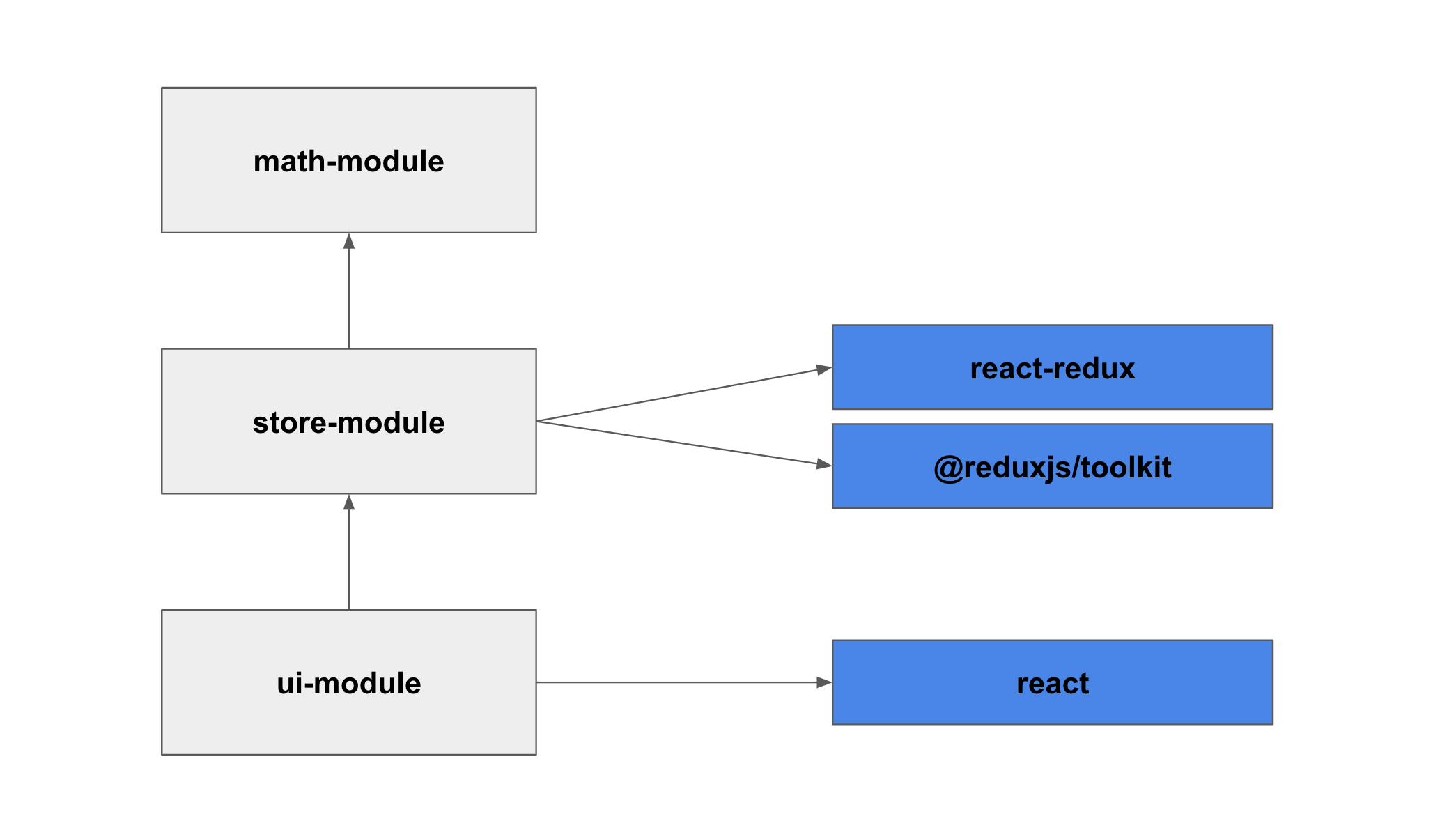

The dependency graph between modules is as follows. Note that the dependency between modules is marked with an arrow, the internal modules are colored grey, and the external packages are blue.

To implement the schema above, we will create three different fenced directories: math, store, and ui. Each directory maps to one of the modules in the schema.

In order to prevent other modules from reaching into the implementation details (or types) of either module, each fenced directory only allows imports from the index.ts files. Implementation details and helper utils remain safe to change as long as the public APIs defined on the index.ts files are not modified.

Also, to prevent circular or unwanted dependencies (for example, the ui depending on the logic directly), each fence is tagged and defines which other fences it can import from.

Finally, to mitigate the issue of unchecked third-party imports, each fence will expressly declare which third-party packages allow imports. New package additions will require modifying the fence.json files, making those dependencies explicit.

The fence configurations for our project are as follows:

// ./math/fence.json

{

"tags": ["math-module"],

"exports": ["index"],

"imports": [],

"dependencies": []

}

// ./store/fence.json

{

"tags": ["store-module"],

"exports": ["index"],

"imports": ["math-module"],

"dependencies": ["react-redux", "@reduxjs/toolkit"]

}

// ./ui/fence.json

{

"tags": ["ui-module"],

"imports": ["store-module"],

"dependencies": ["react"]

}For an in-depth explanation of the fence configuration options, you can check the official documentation.

All those rules can be checked programmatically by running the good-fences npm package, pointing towards the tsconfig.json file of the project (yarn good-fences on the project).

You can now run the checks as part of your CI/CD pipelines or as commit hooks! 🎉

Conclusion

Thanks for sticking until the end!

Proper dependency management and following the architectural design during implementation are vital aspects of a healthy and maintainable codebase.

good-fences is not a silver bullet for this complex topic but rather a great tool to have at hand. As your project grows, it is easy to automate manual dependency-rule checking and encourages the team to be intentional about dependencies (I think this is a great idea!).

The code is available in the following repo; feel free to change and explore it further.

Happy coding! 🚀

- Previous: Date-strings in TypeScript

- Next: Typing CSS Modules